Colonel Burnaby on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Burnaby was born in

Frederick Burnaby was born in

On arrival back in England, March 1876, he was received by Commander-in-Chief,

On arrival back in England, March 1876, he was received by Commander-in-Chief,

A tall

A tall

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (3 March 1842 – 17 January 1885) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

intelligence officer. Burnaby's adventurous spirit, pioneering achievements, and swashbuckling courage earned an affection in the minds of Victorian imperial idealists. As well as travelling across Europe and Central Asia, he mastered ballooning, spoke a number of foreign languages fluently, stood for parliament twice, published several books, and was admired and feted by the women of London high society. His popularity was legendary, appearing in a number of stories and tales of empire.

Early life

Frederick Burnaby was born in

Frederick Burnaby was born in Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

, the son of the Rev. Gustavus Andrew Burnaby of Somerby Hall, Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, and canon of Middleham

Middleham is an English market town and civil parish in the Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire. It lies in Wensleydale in the Yorkshire Dales, on the south side of the valley, upstream from the junction of the River Ure and River Cover. ...

in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

(d. 15 July 1872), by Harriet, sister of Henry Villebois of Marham House, Norfolk (d. 1883). His sister Mary married John Manners-Sutton. He was a first cousin of Edwyn Burnaby and of Louisa Cavendish-Bentinck

Caroline Louisa Cavendish-Bentinck (née Burnaby; baptised 5 December 18326 July 1918) was the maternal grandmother of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, great-grandmother of Elizabeth II, and great-great-grandmother of King Charles III.

Early lif ...

. Fred was educated at Bedford School

:''Bedford School is not to be confused with Bedford Girls' School, Bedford High School, Bedford Modern School, Old Bedford School in Bedford, Texas or Bedford Academy in Bedford, Nova Scotia.''

Bedford School is a public school (English indep ...

, Harrow, Oswestry School

Oswestry School is an ancient public school (English independent day and boarding school), located in Oswestry, Shropshire, England. It was founded in 1407 as a 'free' school, being independent of the church. This gives it the distinction of b ...

, where he was a contemporary of William Archibald Spooner

William Archibald Spooner (22 July 1844 – 29 August 1930) was a British clergyman and long-serving Oxford don. He was most notable for his absent-mindedness, and for supposedly mixing up the syllables in a spoken phrase, with unintentionally ...

, and in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Legend has it he could carry two boys under both arms up the stairs of school house. Burnaby was a huge man for his times: 6 ft 4in tall and 20 stone when fully grown. His outsize personality and strength became the literary legend of imperial might. Lionised by the press for his outlandish expeditious adventures across Central Asia, Burnaby at 6 ft 4 ins tall with broad shoulders was a giant amongst men, symbolic of a Victorian celebrity, feted in London society.

He entered the Royal Horse Guards

The Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (The Blues) (RHG) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, part of the Household Cavalry.

Raised in August 1650 at Newcastle upon Tyne and County Durham by Sir Arthur Haselrigge on the orders of Oliver Cr ...

in 1859. Finding no chance for active service, his spirit of adventure sought outlets in balloon ascents and in travels through Spain and Russia with his firm friend, George Radford. In the summer of 1874 he accompanied the Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimists (disambiguation), Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbon dynasty ...

forces in Spain as correspondent for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', but before the end of the war he was transferred to Africa to report on Gordon's expedition to the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

. This took Burnaby as far as Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

.

Military adventures

Returning to England in March 1875, he formulated his plans for a journey on horseback to theKhanate of Khiva

The Khanate of Khiva ( chg, ''Khivâ Khânligi'', fa, ''Khânât-e Khiveh'', uz, Xiva xonligi, tk, Hywa hanlygy) was a Central Asian polity that existed in the historical region of Khwarezm in Central Asia from 1511 to 1920, except fo ...

through Russian Asia, which had just been closed to travellers. War had broken out between the Russian army and the Turcoman tribesmen of the desert. He planned to visit St. Petersburg to meet Count Milyutin, the Minister of War to the Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

. Travelling at his own expense carrying an 85 lb pack, he departed London Victoria station

Victoria station, also known as London Victoria, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Victoria, in the City of Westminster, managed by Network Rail. Named after the nearby Victoria Street (not the Qu ...

on 30 November 1875. The Russians announced they would protect the soldier along the route, but to all intents and purposes this proved impossible. The accomplishment of this task, in the winter of 1875–1876, with the aim of reciprocity for India and the Tsarist State, was described in his book ''A Ride to Khiva'', and brought him immediate fame. The city of Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

was inaccessible, but presented a potential military flashpoint. The Russians knew that British Intelligence gathered information along the frontier. Similar expeditions had taken place under Captain George Napier

Colonel George Napier (11 March 1751 – 13 October 1804), styled "The Honourable", was a British Army officer, most notable for his marriage to Lady Sarah Lennox, and for his sons Charles James Napier, William Francis Patrick Napier and George ...

(1874) and Colonel Charles MacGregor

Major General Sir Charles Metcalfe MacGregor KCB CSI CIE (12 August 12, 1840 – 5 February 1887) was a British explorer, geographer and officer of the British Indian Army. He was the Quartermaster General for the British Army in India, the ...

(1875). By Christmas, Burnaby had arrived at Orenburg

Orenburg (russian: Оренбу́рг, ), formerly known as Chkalov (1938–1957), is the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Ural River, southeast of Moscow. Orenburg is also very close to the Kazakhstan-Russia bor ...

. In receipt of orders prohibiting progress into Persia from Russian-held territory, he was warned not to advance. A fluent Russian speaker, he was not coerced; arriving at a Russian garrison, the officers entertaining the former Khan of Kokand.

Hiring a servant and horses his party trudged through the snow to Kazala, intending a crossing into Afghanistan from Merv. Extreme winter blizzards brought frostbite, treated with "naphtha", a Cossack emetic. Close to death, Burnaby took three weeks to recover. Having received conflicted accounts of the dubious privilege of Russian hospitality it was a welcome release, he later told his book, to be cheered with vodka. It was another 400 miles south to Khiva, when he was requested to divert to Petro Alexandrovsk, a Russian fortress garrison. Lurid tales of wild tribesmen awaiting his desert travails ready to "gouge out his eyes" were intended to discourage. He ignored the escort, believing the tribes more friendly than the Russians. Intending to go via Bokhara

Bukhara ( Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and the city h ...

and Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

, he deviated, cutting two days off the journey. Leaving Kazala on 12 January 1876 with a servant, guide, three camels and a ''kibitka

A kibitka (, from the Arabic "kubbat" - dome) is a pastoralist yurt of late-19th-century Kyrgyz and Kazakh nomads.

The word also refers to a Russian type of carriage or sleigh.

The kibitka uses the same equipage as the troika but, unlike t ...

'', Burnaby bribed the servant with 100 Roubles a day to avoid the fortress where he would be bound to be delayed. A local mullah wrote an introduction note to the Khan, and clad in furs they traversed the freezing desert. On the banks of River, 60 miles from the capital, he was met by the Khan's nobleman, who guided the escort into the city. Burnaby's book outlined in some detail the events of the following days, the successful outcome of the meetings, and the decision he took to evade the Russian army. The Khanate was already at war, his possessions seized; the Russians intended a march from Tashkent to seize Kashgar

Kashgar ( ug, قەشقەر, Qeshqer) or Kashi ( zh, c=喀什) is an oasis city in the Tarim Basin region of Southern Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan ...

, Merv and Herat. Protestations of neutrality were a sham. Burnaby gained respect from the population, who bowed in homage at a soldier ''en passant''. But on return to his quarters he received a note of orders from Horse Guards to return via Russia. Frustrated Burnaby learnt of the overwhelming numerical superiority the Tsarists presented. To his great surprise he was received as a brother officer at Petro Alexandrovsk. Colonel Ivanov was smug and proud declared the fate of Merv "must be decided by the sword." Released by the Khan's Treasurer he travelled for nine days with Cossacks across the snowy plains of Kazala. Hard-bitten and hungry he sat on a small pony for 900 miles. ''En route'' he heard of what later was described in parliament as the Bulgarian Horrors, and a forthcoming campaign against Yakub Beg

Muhammad Yaqub Bek (محمد یعقوب بیگ; uz, Яъқуб-бек, ''Ya’qub-bek''; ; 182030 May 1877) was a Khoqandi ruler of Yettishar (Kashgaria) during his invasion of Xinjiang from 1865 to 1877. He held the title of Atalik Ghazi (" ...

in Kashgaria.

On arrival back in England, March 1876, he was received by Commander-in-Chief,

On arrival back in England, March 1876, he was received by Commander-in-Chief, Prince George, Duke of Cambridge

Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (George William Frederick Charles; 26 March 1819 – 17 March 1904) was a member of the British royal family, a grandson of King George III and cousin of Queen Victoria. The Duke was an army officer by professio ...

, whose praise marvelled at Burnaby's feats of derring-do and impressive physique. Burnaby's fame grew celebrated in London society, in newspaper and magazines. His guest appearances flattered to deceive, when he learnt that he had travelled with the ringleaders of the Cossack Revolt. The rising of the Eastern Question in parliament was sparked in a village in Hercegovina and spread to Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria. Outraged by the pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s the Prime Minister ordered immediate diplomatic efforts, while W. E. Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

demanded an aggressive clear out of the Sultanate

This article includes a list of successive Islamic states and Muslim dynasties beginning with the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) and the early Muslim conquests that spread Islam outside of the Arabian Peninsula, and continui ...

from Europe. It was in the crucible of this crisis that Burnaby planned a second expedition. At Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

he had planned to meet Count Ignatiev, the Russian ambassador, whom he missed on his journey across Turkey on horseback, through Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, from Scutari to Erzerum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

, with the object of observing the Russian frontier, an account of which he afterwards published. He was warned the Russian garrison had issued an arrest warrant; turning back at the frontier he took ship on the Black Sea via the Bosphorus and the Mediterranean. In April 1877 Russia declared war on Turkey. The inexorable conclusion was drawn in Calcutta and London that Russia would not avoid, but wanted war; planning more attacks still. Eager for Russian rule, Colonel N L Grodekov had built a road from Tashkent to Herat via Samarkand, anticipating a war of conquest. Burnaby's warnings that the bellicose Russians posed a serious threat to India were confirmed later by Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, and an expedition much later under the arabist Colonel Francis Younghusband

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband, (31 May 1863 – 31 July 1942) was a British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer. He is remembered for his travels in the Far East and Central Asia; especially the 1904 British e ...

, witnessed by the genesis of a Cossack invasion.

''See main article: Russo-Turkish War of 1877''

Burnaby (who soon afterwards became lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

) acted as travelling agent to the Stafford House Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

Committee, but had to return to England before the campaign was over.

In 1879 he married Elizabeth Hawkins-Whitshed

Elizabeth Hawkins-Whitshed (26 June 1860 – 27 July 1934), usually known after her third marriage as Mrs Aubrey Le Blond and to her climbing friends as Lizzie Le Blond, was an Irish pioneer of mountaineering at a time when it was almost unheard ...

, who had inherited her father's lands at Greystones

Greystones () is a coastal town and seaside resort in County Wicklow, Ireland. It lies on Ireland's east coast, south of Bray, County Wicklow, Bray and south of Dublin city centre and has a population of 18,140 (2016). The town is bordered ...

, Ireland. The previously-named Hawkins-Whitshed estate at Greystones is known as The Burnaby to this day. At this point began his active interest in politics, and in 1880

Events

January–March

* January 22 – Toowong State School is founded in Queensland, Australia.

* January – The international White slave trade affair scandal in Brussels is exposed and attracts international infamy.

* February � ...

he unsuccessfully contested Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

in the Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

-Democrat interest, which was followed by a second attempt in 1885.

On 23 March 1882 he crossed the English Channel in a gas balloon

A gas balloon is a balloon that rises and floats in the air because it is filled with a gas lighter than air (such as helium or hydrogen). When not in flight, it is tethered to prevent it from flying away and is sealed at the bottom to prevent t ...

. Having been disappointed in his hope of seeing active service in the Egyptian Campaign of 1882

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

, he participated in the Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

campaign of 1884 without official leave, and was wounded at El Teb

El Teb, a halting-place in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan near Suakin on the west coast of the Red Sea, 9 m. southwest of the port of Trinkitat on the road to Tokar.

In mid-December 1883, the British Prime Minister William Gladstone ordered an eva ...

when acting as an intelligence officer for his friend General Valentine Baker

Valentine Baker (also known as Baker Pasha) (1 April 1827 – 17 November 1887), was a British soldier, and a younger brother of Sir Samuel Baker.

Biography

Baker was educated in Gloucester and in Ceylon, and in 1848 entered the Ceylon Rifles ...

.

Death

The aforementioned events did not deter Burnaby from a similar course when a fresh expedition started up theNile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. He was given a post by Lord Wolseley, involved first in the skirmish at El Teb, until he met his death in the hand-to-hand fighting of the Battle of Abu Klea

The Battle of Abu Klea, or the Battle of Abu Tulayh took place between the dates of 16 and 18 January 1885, at Abu Klea, Sudan, between the British Desert Column and Mahdist forces encamped near Abu Klea. The Desert Column, a force of approxim ...

. As a gap in the lines opened up the Colonel rushed out to rescue a colleague and was wounded outside the square. Corporal Mackintosh went to his rescue driving his bayonet into the assailant. Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Binning rushed out to give him some water, twice. On the last occasion he came across a private crying, holding the dying man's head. He had been struck again by a Mahdist spear through the neck and throat. The young soldier was tearful because Burnaby was revered as one of the great Victorian heroes. A courageous man of charm and supreme self-sacrifice, who was admired and respected in equal measure. Lord Binning recalled "that in our little force his death caused a feeling akin to consternation. In my own detachment many of the men sat down and cried". Private Steele who went to help him won the Distinguished Conduct Medal

The Distinguished Conduct Medal was a decoration established in 1854 by Queen Victoria for gallantry in the field by other ranks of the British Army. It is the oldest British award for gallantry and was a second level military decoration, ranki ...

. There are two memorials erected to his memory in Holy Trinity Garrison and Parish Church in Windsor, the first by the officers and men of the Royal Horse Guards and the second, a privately funded memorial from Edward, Prince of Wales.

Cultural references

Henry Newbolt

Sir Henry John Newbolt, CH (6 June 1862 – 19 April 1938) was an English poet, novelist and historian. He also had a role as a government adviser with regard to the study of English in England. He is perhaps best remembered for his poems "Vit ...

's poem "Vitaï Lampada

Sir Henry John Newbolt, CH (6 June 1862 – 19 April 1938) was an English poet, novelist and historian. He also had a role as a government adviser with regard to the study of English in England. He is perhaps best remembered for his poems "Vit ...

" is often quoted as referring to Burnaby's death at Abu Klea; "The Gatling

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a cyc ...

's jammed and the Colonel's dead...", (although it was a Gardner machine gun which jammed). It was, perhaps, because of an impromptu order by Burnaby (who, as a supernumerary

Supernumerary means "exceeding the usual number".

Supernumerary may also refer to:

* Supernumerary actor, a performer in a film, television show, or stage production who has no role or purpose other than to appear in the background, more commonl ...

, had no official capacity in the battle) that the Dervishes managed to get inside the square. Yet the song "Colonel Burnaby" was written in his honour and his portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London. There are two contradictory accounts:

# The report in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', says that Burnaby fell while re-forming a broken British square, this being one of only two recorded cases of a British square breaking in the 19th century.

# Another account says that the square did not break, but men were ordered to pull aside temporarily to let the Gardner gun and then the Heavy Camel Corps get out and attack the enemy. Some Dervishes got inside before the gap closed, but the back ranks of the square faced-about and made an end of the intruders.

Burnaby's ''Ride to Khiva'' appears in Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

's 1898 short story, "Youth

Youth is the time of life when one is young. The word, youth, can also mean the time between childhood and adulthood ( maturity), but it can also refer to one's peak, in terms of health or the period of life known as being a young adult. You ...

," when the young Marlow recounts how he "read for the first time ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is an 1831 novel by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 – August ...

'' and Burnaby's ''Ride to Khiva''," preferring "the soldier to the philosopher at the time."

Burnaby appears as a balloonist in Julian Barnes

Julian Patrick Barnes (born 19 January 1946) is an English writer. He won the Man Booker Prize in 2011 with ''The Sense of an Ending'', having been shortlisted three times previously with '' Flaubert's Parrot'', ''England, England'', and '' Art ...

's memoir ''Levels of Life'' (2014), where he is portrayed as having a (fictional) love affair with Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

.

It has been suggested that Burnaby may have been (in part) an inspiration for the creation of George MacDonald Fraser

George MacDonald Fraser (2 April 1925 – 2 January 2008) was a British author and screenwriter. He is best known for a series of works that featured the character Flashman.

Biography

Fraser was born to Scottish parents in Carlisle, England, ...

's fictional anti-hero Harry Flashman

Sir Harry Paget Flashman is a fictional character created by Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) in the semi-autobiographical ''Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857) and later developed by George MacDonald Fraser (1925–2008). Harry Flashman appears in a ...

.

Works

* ''Practical Instruction of Staff Officers in Foreign Armies'', published 1872 * ''A Ride to Khiva: Travels and Adventures in Central Asia'' (1876) * ''On Horseback Through Asia Minor'' (1877) (both with an introduction byPeter Hopkirk

Peter Stuart Hopkirk (15 December 1930 – 22 August 2014) was a British journalist, author and historian who wrote six books about the British Empire, Russia and Central Asia.

Biography

Peter Hopkirk was born in Nottingham, the son of Frank St ...

)

* ''A Ride across the Channel'', published 1882

* ''Our Radicals: a tale of love and politics'', published 1886

;Journals

* Regular contributions as roving correspondent to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' in Egypt and the Sudan

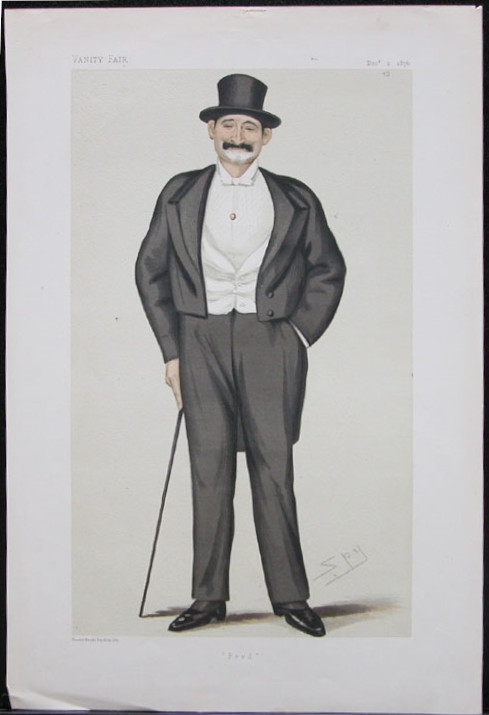

* '' Vanity Fair''

* ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' from 1872 onwards.

;Letters

* edited by Dr. John W. Hawkins, ''Fred: The Collected Letters and Speeches of Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby. Vol. 1 1842-1878'' (Helion & Co., 2013)

* ed. Dr. John W. Hawkins, ''Fred: The Collected Letters and Speeches of Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby. Vol. 2 1878-1885'' (Helion & Co., 2014)

Legacy

Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

obelisk in the churchyard of St Philip's Cathedral, Birmingham

The Cathedral Church of Saint Philip is the Church of England cathedral and the seat of the Bishop of Birmingham. Built as a parish church in the Baroque style by Thomas Archer, it was consecrated in 1715. Located on Colmore Row in central Birmin ...

commemorates his life. Besides Burnaby's bust, in relief, it carries only the word "Burnaby", and the dated place names "Khiva 1875" and "Abu Klea 1885". The obelisk was unveiled by Lord Charles Beresford

Admiral Charles William de la Poer Beresford, 1st Baron Beresford, (10 February 1846 – 6 September 1919), styled Lord Charles Beresford between 1859 and 1916, was a British admiral and Member of Parliament.

Beresford was the second son of ...

on 13 November 1885.Roger Ward, ''Monumental Soldier'', in

There is a memorial window to Burnaby at St Peter's Church, Bedford

The Parish Church of St Peter de Merton with St Cuthbert is an Anglican church on St Peter's Street in the De Parys area of Bedford, Bedfordshire, England.

History

The site has been used for Christian worship for more than a millennium. Althou ...

. There is also a public house, The Burnaby Arms, located in the Black Tom area of Bedford. The organ at Oswestry School

Oswestry School is an ancient public school (English independent day and boarding school), located in Oswestry, Shropshire, England. It was founded in 1407 as a 'free' school, being independent of the church. This gives it the distinction of b ...

Chapel was given in his memory.

William Kinnard, who was instrumental in acquiring a post office for a tiny settlement at the base of Morgan's Point

Morgan's Point is located 30 miles east of Houston in Harris County, Texas, United States, located on the shores of Galveston Bay at the inlet to the Houston Ship Channel, near La Porte and Pasadena. As of the 2010 census, it had a population ...

on Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

's North Shore in Ontario, Canada, "suggested the name Burnaby after an article he had read in The Globe" newspaper about a Colonel who had been killed in the Egyptian War.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *Secondary sources

*(Andrew, Sir William ?) "An Indian Officer", Russia's March towards India, 1894 * * * * * * * Chapter 10 - "Fred Burnaby: The Gentle Giant"External links

* — biography of a Frederick Burnaby * {{DEFAULTSORT:Burnaby, Frederick Gustavus 1842 births 1885 deaths British colonels Military personnel from Bedford People from Bedford People from the Borough of Melton People educated at Harrow School Royal Horse Guards officers English travel writers British military personnel killed in the Mahdist War People educated at Oswestry School Greystones The Great Game People educated at Bedford School